On Addy Turning Thirty: Why Her Life Still Matters

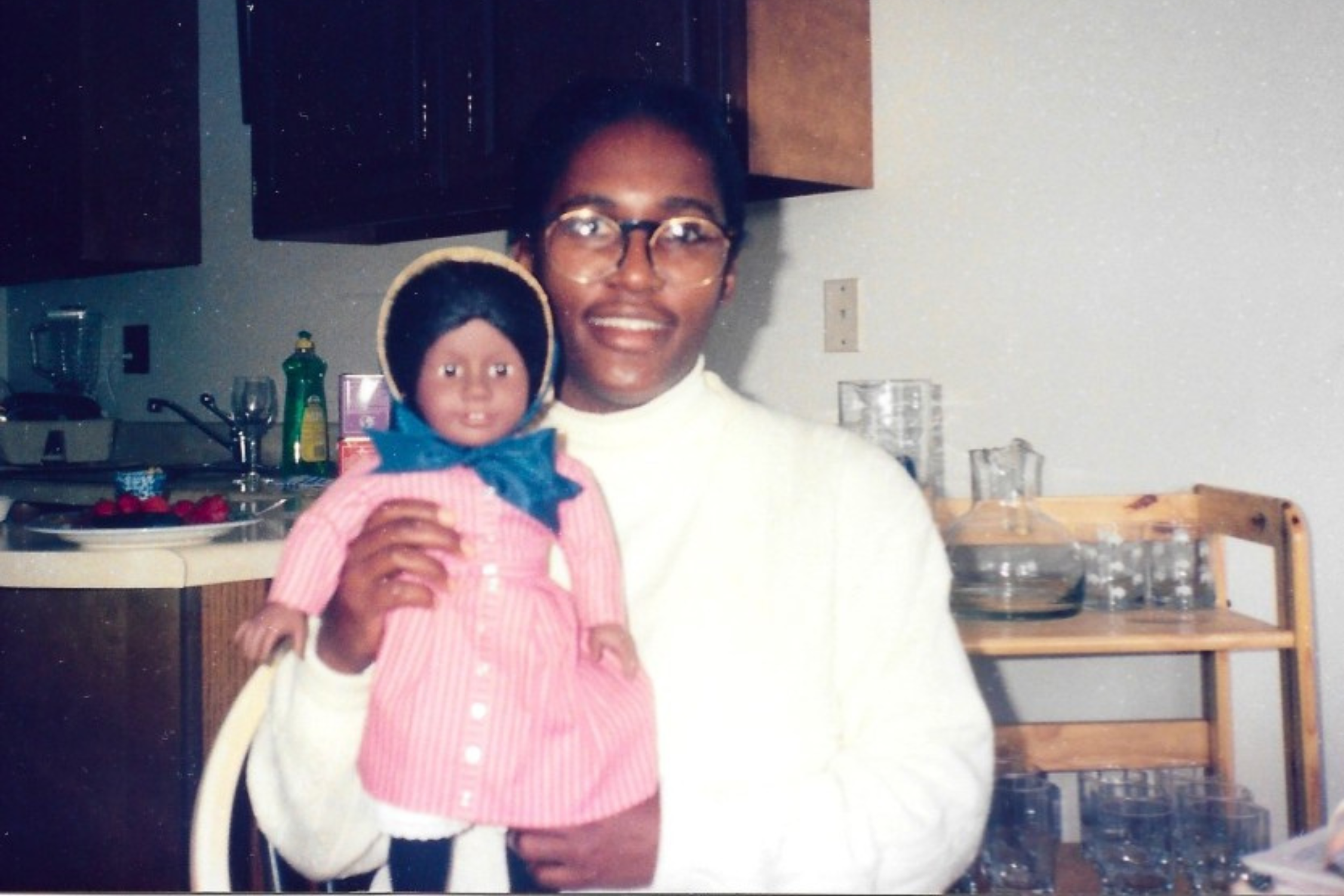

Image Caption from Connie Porter: My Initial introduction to Addy before I started writing the series.

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the launch of the Addy series, and as life has a way of bringing us in circles, taking us around to get another view of who we are and where we have travelled, I am sitting here in North Carolina writing this piece from my home, just a piece down the road from where the Addy series begins. Lush, green tobacco fields push up against the edges of narrow, two-lane roads, tall stands of pines bend in the wind and bow to history. Heat, and humidity haunt summers, and cold and punishing rain pelts in winter.

To be perfectly honest, my vision for this series did not extend 30 years into the future. It extended backwards into Addy Walker’s world—into enslavement, the Civil War, the world of limited freedoms of African Americans in the North pre and post war. It extended into the life of a nine-year-old girl who was courageous, hopeful and bright, and who wanted to live in freedom with her family.

When I look back at the life of Addy these past thirty years, sometimes I wonder if there were too many expectations placed on the slender shoulders of one nine-year old character. The experience of one character, the story of one character, could not represent the millions of stories of enslaved people whose names rung as clear as bells inside the families who loved them, but have fallen silent and been lost to time.

Over the years I have consistently expressed the core belief I had about my role as the initial author of the Addy series---I wanted to give Addy a voice. I saw her, and still see her as representing a life among the millions of lives of enslaved people who were nameless, faceless and voiceless. Addy’s life mattered.

From the launch of the Addy series, there were critics and some sense of skepticism that Addy and her line of merchandise was merely a way for a white company to exploit slavery. Though the belief was argued, what was hard for critics to counter the authenticity of the story, the quality of the project.

One of the major reasons I chose to work with Pleasant Company was the fact that the founder, Pleasant Rowland was committed to the Addy project, and knowing the limitations of the company, included an African American advisory board. The board included Lonnie G. Bunch, who went onto become the founding Director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. (He stepped down in 2019 and currently is the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution). Pleasant risked her capital, her reputation and that of her company in launching Addy.

What was also hard for critics to argue, to counter, was the way the African American community embraced Addy. Through the brilliant illustrations of Melodye Benson Rosales, African Americans, saw a face, felt a spirit. Through my words, they heard a voice that spoke to them. Addy Walker was, is, that ancestor we have reclaimed.

Given the attempt of some politicians, some groups who want to trivialize the importance of African American history, or to erase it completely, I feel now more than ever that African Americans should embrace our history, and so should all of America. All of it. It holds no shame for me. Our lives, culture, history, gifts skills and talents did not begin here. The stories about Addy are about one child. I know that some may not want to hear her story, to talk about, the untold millions of stories of enslaved people. Even some African Americans feel this way. I can honestly say, I understand it. I get the weariness, but I feel I am no more weary than the earliest relative we have been able to trace in our family, Hannah Dunn who was born a slave in 1850 in Alabama. The irony is that she would have been a contemporary of Addy, and she was my mother’s grandmother.

If I can speak with love and reverence of my mother to my daughter, I can speak of the love and reverence my mother had for her grandmother, a woman she never knew. And I can speak of Addy. We can all still speak of Addy. For the past thirty years, we have heard her voice, seen her face. Her story, risen from the dust, has brought me, brought her readers full circle to meet an ancestor.