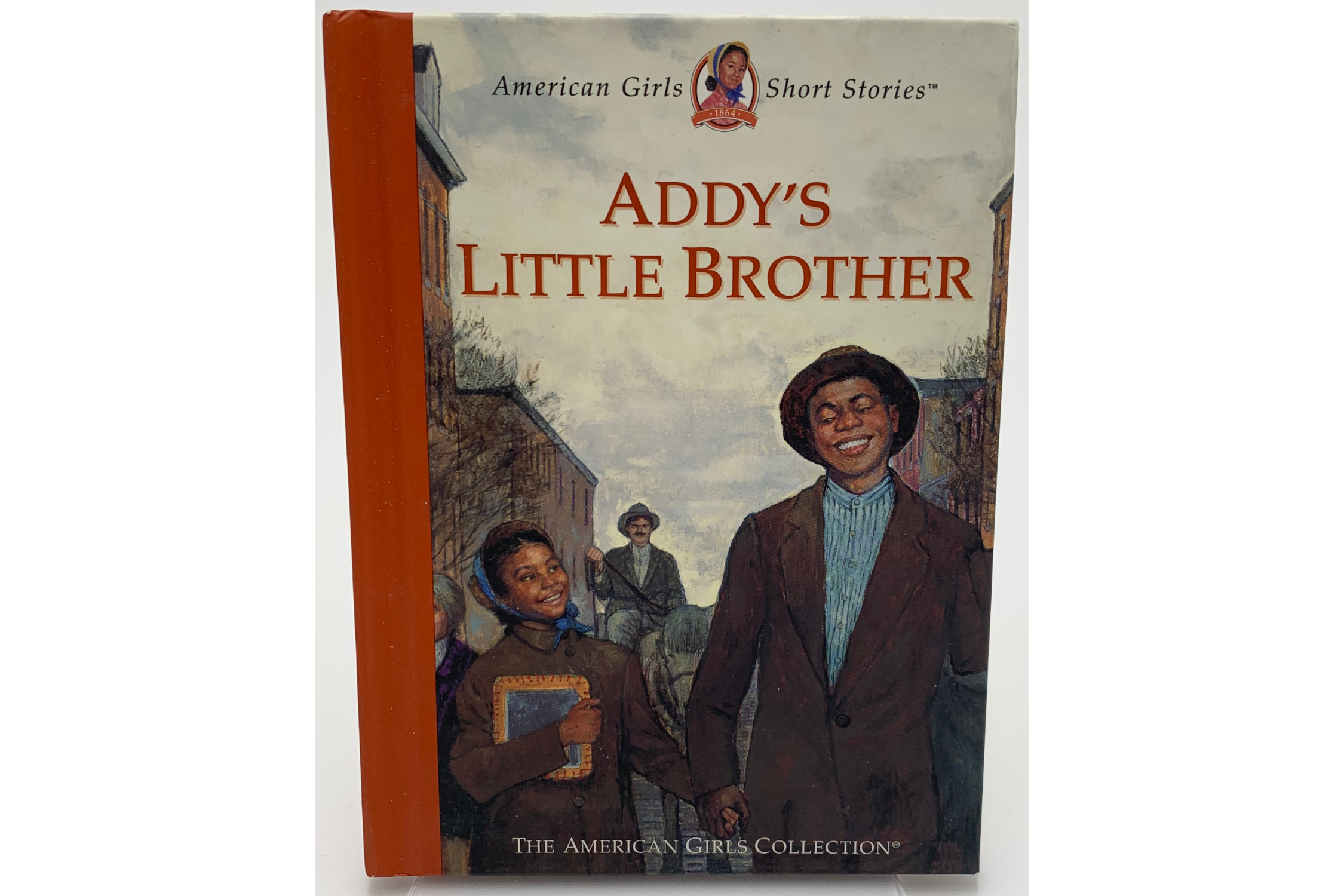

Addy’s Little Brother

In Addy’s Little Brother, “After her brother joins the family in Philadelphia at the end of the Civil War, Addy wants to be with him as much as possible, so she is jealous when he starts spending time with her friend's cousin.” (Connie Porter, 1999, 2000)

Click each photo below to explore each item in this display.

Classic Addy’s Plaid Summer Dress

Addy’s Little Brother

Looking Back: African American Churches During and After the Civil War

By: Leah Jenkins, Assistant Researcher

African Americans and their relationships with Christianity were defined by era and location. In the South, enslaved owners were initially apprehensive of allowing enslaved individuals to convert to Christianity in fear that it would elicit the idea of equality. Legislation was even created declaring baptisms were unable to free enslaved individuals. Eventually, slave owners saw the possibility of total control and allowed enslaved individuals into churches.

In the 1830s and 1840s, church plantations surfaced where ministers preached slave loyalty to their captors. Tired of concealed intentions, enslaved people congregated to “hush harbors” in the woods, cabins, gullies and ravines to worship. Meanwhile, in the North, Black individuals had more agency over their religious affairs. The creation of Black societies gave way to independent Black churches of multiple denominations. In the early 1800s, the first Black protestant church, The African Methodist Episcopal (AME), was founded by Richard Allen. Black churches like AME worked with Black societies to organize the Underground Railroad.

Federal legislation affirmed African American civil rights and supported Black churches’ societal power. Churches were where Black Americans constructed and defined their body politic. Initially, Black churches like the AME sent missionaries south to assist in teaching reading and math. Black churches shifted again in the early twentieth century when a great migration of Southerners north transformed black protestant churches. Blues music, hymns and choirs emerged in northern Black churches. Churches maintained social significance into the twentieth century as these places of worship were the backbone of civil rights.

References: